This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: Hello. I'm Kathrin LaFaver. I'm a movement disorder specialist in Saratoga Springs, New York. I have the pleasure of talking today with Dr Indu Subramanian, a clinical professor at UCLA in California and the first author of a paper just published in Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, entitled "Delivering the Diagnosis of Parkinson's Disease – Setting the Stage With Hope and Compassion."

I love the title. To start it off, do you want to tell us about what gave you the motivation to look into this topic?

Listening to Patient Voices

Indu Subramanian, MD: During the pandemic, I was hosting a virtual support group with a number of voices throughout the world who are thought leaders in the care of Parkinson's patients. Some of the discussions included a number of patient voices, and I became involved in some of the advocacy community, learning about what has served patients well in terms of what we do and what they found somewhat harmful in terms of what we've done as a treatment team sometimes.

I was actually quite surprised at how impactful some of the conversations were around how people got the diagnosis. For example, Kuhan, who is one of the authors, is a patient who lives in the UK. He's a young Sri Lankan man.

He was talking about the day that he got the diagnosis with such clarity, such pristine memories of the sky, the light, the paint in the office. This is a moment in time that is frozen. Now, 10 years later, he looks back on that as a really pivotal moment for him and recalls it sometimes with negative energy and thinks it could have been done better.

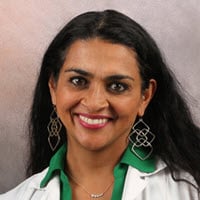

Soania Mathur, who's an amazing patient voice as well, is actually a family doctor who has practiced in Canada and talked about how we can do better. We ended up pairing with some of these patient voices and also some world leaders in this space.

Bart Post is a neurologist who is very interested in early-onset or young-onset Parkinson's disease and runs a center in the Netherlands. Anette Schrag, who is the senior author, devoted a number of years of her career to learn how patients could perhaps create plans for self-management. She's had a number of interviews and focus groups with patients, and much of the data in our paper are from her.

Did they feel like the disease diagnosis was given with compassion? Did they feel like they got these types of information? What do they walk out of the office understanding? What are the lifestyle choices they can make?

It was a really nice collaboration. We also had included a psychologist in the paper who could fill in some of the psychology of getting bad news.

Prescribing Hopamine

LaFaver: Why don't you tell us about the main goals and the writing process, given that such a diverse group of people was involved?

Subramanian: It's a paper that I'm really proud of because I think the underpinnings of the paper are direct quotes from the patient voices. We have Kuhan, for example, in his own words talking about how he wished it had gone differently. Some of his advocacy work is now helping newly diagnosed patients with their diagnosis and to move forward in a constructive way to feel positive about the years that they have to live with Parkinson's and what they can do to live better. I urge you to read that.

Soania brings in some of her advocacy work, what she's learned from being a person living with Parkinson's, and educating other folks for the past 20 years.

Then, we looked at the data to see what has been spoken about. One part of the paper also talks about the work of Bas Bloem and a colleague of his who wrote a paper about hopamine as a pill that we should be administering. They talk about the fact that a physician/clinician has a responsibility to bring some hope to an encounter like this, but then to also allow the person living with the disease to formulate their own sense of hope that may apply to their own process.

For a person living with this disease, it might take some time to develop that hope. Giving false hope or empty words at the beginning and using words like, for example, "the honeymoon period," was also dispelled in another paper by Bas and co-authors as something that we shouldn't be using. We shouldn't be using the term "honeymoon period."

That doesn't land well with our patients. In such a serious disease state, at no point is this really a honeymoon or an amazingly pleasant experience. We should be really mindful of some of the words that we, as a community of neurologists, are picking and how they land with the people living with this disease.

LaFaver: That's a good point. The paper outlines a number of different graphs, tables, and key points to consider when giving someone a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Could you walk us through the process and some of the key points that you think are most important?

Subramanian: First of all, I want to say that this is not a paper to make clinicians feel bad. I think you and I, Kathrin, realize that the healthcare system as it exists is effectively broken. We as clinicians are being asked to do more and more very complex work, managing patients that are very sick, often with not much support.

We are asked to do this in a smaller and smaller time frame, along with increasing demands for documentation. I am not here to judge anyone's work. This paper is just to say that this is how giving this diagnosis in a certain manner can affect the trajectory of a patient for decades to come.

If we do this with a sense that these words matter, that this time frame matters, and that those 15 minutes that we have with the patient matter… The way that we're expressing this, the way that we're able to connect with the patient one on one to give them that time to really understand these words to reflect back to us what they're feeling… And for us to then, again, give them resources that they can use until the next time we meet them. I think these are all important takeaways.

First and foremost, it's important to have a quiet space and have protected time. We're seeing patients who are often frazzled, and no one else is there to really take down the information or to advocate for the patient and support the patient once we leave the room. I really have been trying to get patients to bring a loved one or a trusted friend who can be an extra set of eyes and ears, who is able to write things down and then support that patient.

Much of my research has been on the need for support and social connection as a buffer. Honestly, from day 1 of disease, I think that it can really matter. If it is a rushed encounter at the first visit, we should allow the patient to reschedule a visit where you have more time and bring in a loved one at that time, if it's possible. At that first visit, we don't have to give every piece of information that ever existed on Parkinson's.

Other considerations include delivering the diagnosis, rescheduling an appointment, or perhaps engaging another member or two of the team if you have a nurse. Some places have a Parkinson's 101 class. Some of the support groups have a support group leader who may be able to take that person on and match them with somebody who's a little further on in the disease course, who can then serve as a support to the person.

I think it's important to understand that these words matter, this time matters, and how we deliver the disease matters. There is hope. There are things that the person living with the disease can do every day in terms of lifestyle choices.

You have a very treatable disorder. If you can start exercising, if you can get some social connection, find somebody to connect with every day, good sleep, good hydration, eating right, and incorporate some self-care time with some mind-body approach time, perhaps — some yoga, some meditation, prayer — all of these, I think, can be things that the patient feels they can do proactively until the next visit.

What people living with this disease are often hearing — and this may not be what is actually said — but what they're taking away is, "Here's a pill. Come back in 6 months." They feel highly unsupported, and often then google "Parkinson's" and end up going down rabbit holes that are very negative.

Have the patient leave the office feeling like we are part of the team. We are going to work together for years to come, and we're here for you. Here's a support group, if that's available to you, or here are some lifestyle choices. Let's continue the dialogue.

Also, we need to normalize the reactions that can happen. In our paper, we wrote a number of bubble diagrams of normal reactions, including anger, fear, frustration, grief, anxiety, and depression. You have a disorder, Parkinson's disease, that already has many mental health issues that come along with it. The reaction to the diagnosis can really exacerbate some of these issues.

Normalizing these reactions, just like if we had given a diagnosis of cancer or a terminal illness, the sense that a person may go through some reactions is actually very common. If you're that person living with the disease and then you don't realize that what you're feeling is a normal reaction, you can then feel more isolated and not feel like there's anyone to really help you.

LaFaver: One of the issues I'm hearing is the need to offer better relative short-term follow-up. It's certainly something I have tried to incorporate more in my own practice. I used to usually see people after 3 months or so. Currently, when I do see someone, and especially when I start them on a medication, I try to offer a 6-week follow-up. I've definitely found it very helpful.

As you said, sometimes with a first visit, it can be an information overload. It can be hard to find that balance of explaining enough but also not overwhelming patients. Trying to see them back relatively soon, to give additional resources that are reliable, and possibly even having a support element, I think, can be very helpful.

What was really pointed out in the paper was being sensitive to someone's cultural background when giving this diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Could you give me some examples of how that would come into play in clinical practice?

Subramanian: We wrote a sister paper to this about stigma. For example, in Hindu culture, when somebody gets news of a disease state, there's a sense that karma — something that we did in our previous life or in this life — led to this diagnosis occurring. People sometimes have some self-blame and shame and often won't even tell their own family members or extended family members about the diagnosis, because of this negative attribution for why they got the disease.

Understanding a patient's understanding of their disease state, what happened, and why this could have happened, and that nothing they did, to our knowledge, caused this is actually good to state to dispel those myths.

The African diaspora, in Africa itself, there's been a sense that sometimes there's a witchcraft element. Somebody's been possessed if they start tremoring, or people are hidden from their communities in back rooms and really are not allowed to socialize.

I think understanding what the mythology is, how this disease affects not only the person living with it but their family dynamic, can actually be really helpful for delivering care moving forward. If we miss the mark with a single cookie-cutter way of delivering care to everyone, I think we're excluding many people.

We've talked about the fact that women, for example, often don't have the time and feel guilty when they can't take care of other people. They feel really bad if they can't be the caregiver. For them to be in this role of sometimes needing care, needing help, needing social support from their sister, mother, sorority sister, or their daughter, that is an extra layer of something that we need to say is necessary and important and help them build that in.

I think we need to customize this to each person that we see in front of us. For some people, spiritual support from a religious leader is huge. If they get a diagnosis like this, they're going to go talk to their rabbi or their priest, and that's who's going to give them comfort. Understanding who gives you comfort, who is your support mechanism, what is your understanding of why you got this disease, is really, I think, part of what we need to do to help people to do better and to not only live better, but also even thrive in the setting of some of these diagnoses.

Other Diagnoses

LaFaver: I couldn't agree more. I've discovered that some of these myths or beliefs that might be different from what we in the medical community think, come out later, and it's very helpful to ask patients. It doesn't have to be all in the first visit, but we can ask some questions of their understanding of disease and really have that open conversation to try to dispel some of these myths, as you mentioned.

We're talking about Parkinson's disease. Do you see any parallels with other immunologic disorders or other issues in the field of medicine we can learn from?

Subramanian: Absolutely. A paper like this hadn't quite been written in Parkinson's, including the patient voices. I think when you read the quotes, you'll realize that this isn't just Parkinson's disease. Insert ALS, insert Alzheimer's disease, many chronic neurologic diseases, and other diseases, too. Some of the framework that we came up with was actually from the cancer literature.

We talk about the SPIKES framework of giving news. Even though we don't have data in our own disease state, we looked at palliative care literature and cancer literature to see what they had and tried to customize it to our patients.

For other disease states that we take care of in neurology, I think we can also utilize this same framework. I want to say that, not only in the disease state, but I think when we look at the settings in which we're all practicing, and who's actually giving the diagnosis — Mike Okun and I wrote a blog about this paper as well.

When you look at the laundry list of all the things that could be done in this interaction, it would take 2 days. We want to start to drizzle some of these ideas in and to incorporate some things in certain interactions, and some things may be more applicable to other interactions.

I think the hope about this paper is really to take a step back and ask how we can set ourselves off on the right footing that, in the long run, may actually help the patient as well as our own rapport with them and how to get them to adopt treatments.

Sometimes our treatments are very complex and require multiple pills, multiple dosing. Many times, we're confused as to why there's a lack of compliance or adoption, or people don't come back to see us. When people feel seen, when people feel heard, when there's a sense that the doctor wants to understand them and meet them where they are, I think that automatically is going to set things off on the right foot. I think we can apply that throughout medicine in general.

LaFaver: Beautiful. Thank you so much for these enlightening words. It was a pleasure talking to you. I encourage everyone to read the paper: "Delivering the Diagnosis of Parkinson's Disease – Setting the Stage With Hope and Compassion," in Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. Thank you again. Have a good rest of your day.

Medscape Neurology © 2024 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Breaking an Unwelcome Diagnosis With Hope and Compassion - Medscape - Feb 28, 2024.

Comments