Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors may delay progression of several chronic kidney diseases in adults. Two classes of RAS inhibitors—angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)—have been shown to have renoprotective abilities. Despite their different mechanisms of action, these two drug classes appear to have comparable antiproteinuric and renoprotective properties. Preliminary investigations suggest that combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor and ARB offers additional benefit. Only a few studies with these drugs for treatment of pediatric nephrology have been conducted; however, their results are encouraging. Additional clinical trials are needed to confirm these results.

Introduction

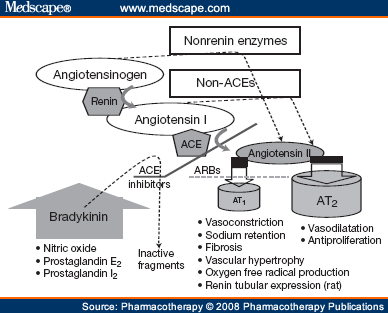

Two classes of antihypertensive drugs that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) are used in clinical practice: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). Both classes limit the hypertensive effects of abnormal angiotensin II production. The ACE inhibitors reduce conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. In contrast, ARBs block the angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1). Inhibition of angiotensin II exerts specific effects in the muscular vasculature of the kidneys,[1] decreasing intraglomerular pressure, improving glomerular-barrier size selectivity, and reducing the amount of proteinuria.[2]

Hemodynamic effects mediated by the two types of angiotensin II receptors—AT1 and AT2—have been investigated in animal models. The net result depends on the activation of AT1-mediated vasoconstriction versus AT2-mediated vasodilatation. In rats with kidney failure, the vasoconstricting action of angiotensin II is not dangerous for the kidneys because it is concomitant with an overexpression of AT2 vasodilatation.[3] Consequently, renal fibrotic changes may develop from different pathways, possibly including mechanisms that do not depend on hemodynamics. For example, angiotensin II probably upregulates expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-b1, which has profibrotic properties. In mice, combination therapy with TGF-b receptor antagonists and RAS inhibitors limited the progression of chronic kidney diseases.[4] Inhibitors of the RAS may act to maintain expression of nephrin, a structural protein of the glomerulus, and preserve the architecture of the kidney.[5] Furthermore, rats with glomerulopathy exhibit an upregulation of key inflammatory mediators. These molecules lead to tissue alteration, including both glomerular matrix accumulation and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, perhaps partly due to an upregulation of AT1, as shown by their reversal after treatment with ARBs.[6] Recent observations have clarified the role of angiotensin II in increasing renin expression in collecting tubules and collecting ducts of the kidney in rats; AT1 was found to mediate the augmentation of renin concentration in rats.[7] Therefore, renin activity contributes to increased levels of intratubular angiotensin II. In contrast, treatment with an ARB prevents overexpression of renin.[7] Consequently, RAS antagonists may act to break down this potential mechanism (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Renin-angiotensin system pathway with sites of action of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARBs), showing main phenotype expressions related to activation of angiotensin II receptors types 1 and 2 (AT1 and AT2).

The pathophysiology of renal injury from angiotensin II is not only due to its vasoconstric-tor action. Angiotensin II mediates a large array of activities through AT1. These include sodium retention,[8] fibrosis,[9] vascular hypertrophy,[10,11] oxygen free radical production,[12] and expression of adhesion molecules.[13] In addition to its hemodynamic actions, angiotensin II has important proinflammatory effects.[14,15] Taken together, the blockade of such actions delays the progression of renal damage.

Several studies have provided evidence of the clinical benefits of angiotensin II blockade. First, the ACE inhibitor ramipril was found to reduce the loss of renal function and delay the progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in patients with nondiabetic renal disease.[16,17] Subsequent investigations suggested that ARBs attenuated the adverse effects of angiotensin II more efficiently than ACE inhibitors. Pathways not involving ACE that generate angiotensin II are inhibited by ARBs but not by ACE inhibitors. These findings suggest that the action mechanisms of ACE inhibitors and ARBs are not identical.[18,19]

Thus, delivery of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in combination may provide clinical benefits that surpass those achieved with either drug alone. In adults, several investigations have found an enhanced antiproteinuric effect of combined ACE inhibitors and ARBs.[20–24] These observations were further reinforced by the Combination Treatment of Angiotensin-II Receptor Blocker and Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibitor in Non-diabetic Renal Disease (COOPERATE) trial, in which combined treatment with the ARB losartan and the ACE inhibitor trandolapril slowed progression of nondiabetic renal disease to a greater extent than either agent alone.[25] Both ACE inhibitors and ARBs are recommended to reduce proteinuria and delay progression of kidney disease in adults.[26] However, their use in children is still limited,[20] and very few data are available for this patient population. Table 1 summarizes the available information from studies of combination therapy with ARBs and ACE inhibitors in pediatric patients.[27–34]

Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(1):125-130. © 2008 Pharmacotherapy Publications

Cite this: New Therapeutic Strategies with Combined Renin- Angiotensin System Inhibitors for Pediatric Nephropathy - Medscape - Jan 01, 2008.

Comments